There are several news stories about this research BBC “Adoption and Care rates vary starkly” , Bureau of Investigative Journalists “Postcode lottery for adoptions” ,CYP Now “Increase in child protection investigations, but fewer finding abuse”, & Spiked “Why are so many children in care”

Adoption and Child Protection Trends for children aged under five in England: Increasing investigations and hidden separation of children from their parents Accepted Manuscript

This study used freedom of information requests with responses from around half of all local authorities to compare involvement with children’s services before their fifth birthday in 2011-12 and 2016-17. 70 local authorities provided information on children adopted before the age of five or in care at 31st March in 2012 and 2017. The number of children adopted and the number subject of section 47 enquiries increased by 50% in just five years. By 2016-17, 6.4% of all five year-olds, one in every sixteen of the more than 350,000 five-year-olds in these authorities, had been subject of investigations.

This study used freedom of information requests with responses from around half of all local authorities to compare involvement with children’s services before their fifth birthday in 2011-12 and 2016-17. 70 local authorities provided information on children adopted before the age of five or in care at 31st March in 2012 and 2017. The number of children adopted and the number subject of section 47 enquiries increased by 50% in just five years. By 2016-17, 6.4% of all five year-olds, one in every sixteen of the more than 350,000 five-year-olds in these authorities, had been subject of investigations.

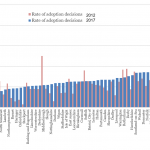

Differences between local authorities in adoptiond and children on placement orders at age 5 in 2012 and 2017

These changes were not evenly distributed and rates of children who had an adoption decision before the age of five, either being adopted or on a placement order at the age of five, varied significantly across the country with a twelve-fold difference between the highest and lowest rates. The graph below shows the rate of children adopted or on a placement order in the 2012 cohort and the 2017 cohort. It shows large disparities between local authorities in the rate of children having a been adopted or waiting for adoption by the age of five with a 12-fold difference between the highest and lowest rates. It also shows that some local authorities had large increases in rates of adoption decisions, some reductions and some had no change or small increases. These differences were not simply due to differences in deprivation. For example Southampton, which had the highest rate of children adopted or on a placement order at the age of five (1.85% of five-year-olds), had significantly higher rates than its ‘statistical neighbours’ in the study.

The twenty local authorities with the biggest increases in adoption decisions had a 96% increase in the number of children adopted or on placement orders in five years. Across these authorities all aspects of children’s services activity had increased more than in the other 50 local authorities with child protection investigations changing most – they increased by 90% and 7.8% of all children were investigated under section 47 before their fifth birthday. The research thus raises the question of why these authorities had such a large change in concerns about significant harm (child protection plans increased by 52% while investigations increased by 90%) and asks the question of why rates of adoption vary so much between local authorities.

The study confirms earlier findings that 1 in 5 children are referred to children’s services before the age of five but shows rapidly increasing levels of child protection investigation and rapidly growing numbers of children separated from their parents when the cumulative effects of adoptions and special guardianship are taken into account. These trends suggest that the impact of reduced funding for family support and the increasing stress put on families through growing inequality are impacting strongly on children and families.